Our tour set out again on the morning of December 28, aboard tuk-tuks once again. The first stop was not far from the Rambutan, at a restaurant where we tried a Cambodian breakfast specialty: a noodle soup called Kuy Teav. Suihong, the trainee guide, explained that it’s not the sort of thing one has every day, but rather a “millionaire breakfast” for special occasions. After that we moved to a street stall nearby for Cambodian doughnuts, which were excellent — and to this old beignet fan, showed a strong French influence.

The next stop was at a food market, which for me was the first real “not in Kansas” moment. We don’t have markets like that in the United States. We have “farmer’s markets” but they are upscale, dealing in farm-fresh and “organic” produce — essentially luxuries. The market in Phnom Penh was a series of metal-roofed sheds with narrow aisles between stalls selling all manner of things. Eggs, meat, fish, vegetables, spices, fish paste, pickles, bottled water, beer, clothing, shoes . . . basically all the necessities.

I got to see fresh lemon grass, galangal (a relative of ginger with a different, sharper flavor), and turmeric root (which we were warned not to handle because it makes an extremely effective yellow dye). Fascinating place, to which I’m sure any health inspector in the Western world would give a “fail with extreme prejudice” rating.

We stopped at a café afterward and I had one of the best cups of coffee I’ve ever drunk in my life. Cambodian coffee is good. They pay a lot of attention to the precise blend of beans and roasts and the result is amazing. Like a whole pot of coffee’s worth of flavor distilled into a single cup.

Then we rode our tuk-tuks south for a stop at one of Cambodia’s most significant historical sites: the S-21 Museum — or to give its full name, the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. It’s called “S-21” because that was the designation given the facility by the Communist Khmer Rouge regime during their period of power in 1975-1979.

It was originally a school, but the Communists turned it into a prison and torture center. This was where they took anyone they deemed problematic, and tortured them until they “confessed” to whatever the Khmer Rouge had already decided they were guilty of.

And then they were taken out of the city (to the famous “killing fields”) and shot, and left to rot.

This was not the worst stuff that the Khmer Rouge got up to in their four-year orgy of ideological cruelty and violence. Not by a long shot. They emptied out the entire city of Phnom Penh, driving three million people out into the countryside to do agriculture with no training and inadequate tools. (And when the crops didn’t meet the Communist fantasy target numbers, the few farmers who did know what they were doing were accused of sabotage and shot.)

I could write ten thousand words on the subject here, but I’m just going to say: this is what “smashing capitalism” actually looks like. Thousands of bodies rotting in a field. If you want to argue, I’m afraid I have no patience left for that any more. Just go ahead and delete the bookmark to my blog right now and save us all a lot of time.

Did I mention the exhibit of the children under 12 years old who were captives in the S-21 prison? Most of whom were eventually shot?

The museum includes tombs of the remains of prisoners found in the building when the Khmer Rouge fled the liberation of Phnom Penh (by the Vietnamese, no less). There’s a self-guided audio tour, including recordings of statements by survivors of the place, and even a few of the guards. You can see the former classrooms, divided up with crude brick and wood partitions into cells too small to lie down in, each housing multiple prisoners. You can see the swing set in the courtyard turned into a torture device. One room is full of skulls.

We all came out of the S-21 museum very quiet.

And then we cheered up with a really good lunch of Banh Hoi, a build-your own Vietnamese dish where you take noodles, cooked meat or sausage, bean sprouts, chili paste, etc., and roll them in a lettuce leaf, dip in sauce, and eat up. A wonderful combination of different flavors and textures — and something which would be quite feasible to make at home. I intend to try it when the weather warms up and we start getting nice big lettuces.

In the evening, the tour went (by tuk-tuk, of course) down to the Phnom Penh waterfront, where we boarded a riverboat for a sunset cruise on the Mekong River. There are a lot of those little riverboats operating off Phnom Penh, all decorated with big light-up signs advertising local beers (Hanuman and Ganzberg seem to be the heavyweights in the boat-sign sector). Some of them seem to serve as ferries, but apparently most of them are party boats. I saw a few set up for dinner cruises, and to be candid I kind of wished we had done that. It’s nice and cool out on the water — the Mekong comes down from the Himalayas, after all — and since the river is east of the city you can watch the sun go down behind Phnom Penh’s skyscrapers and pagodas.

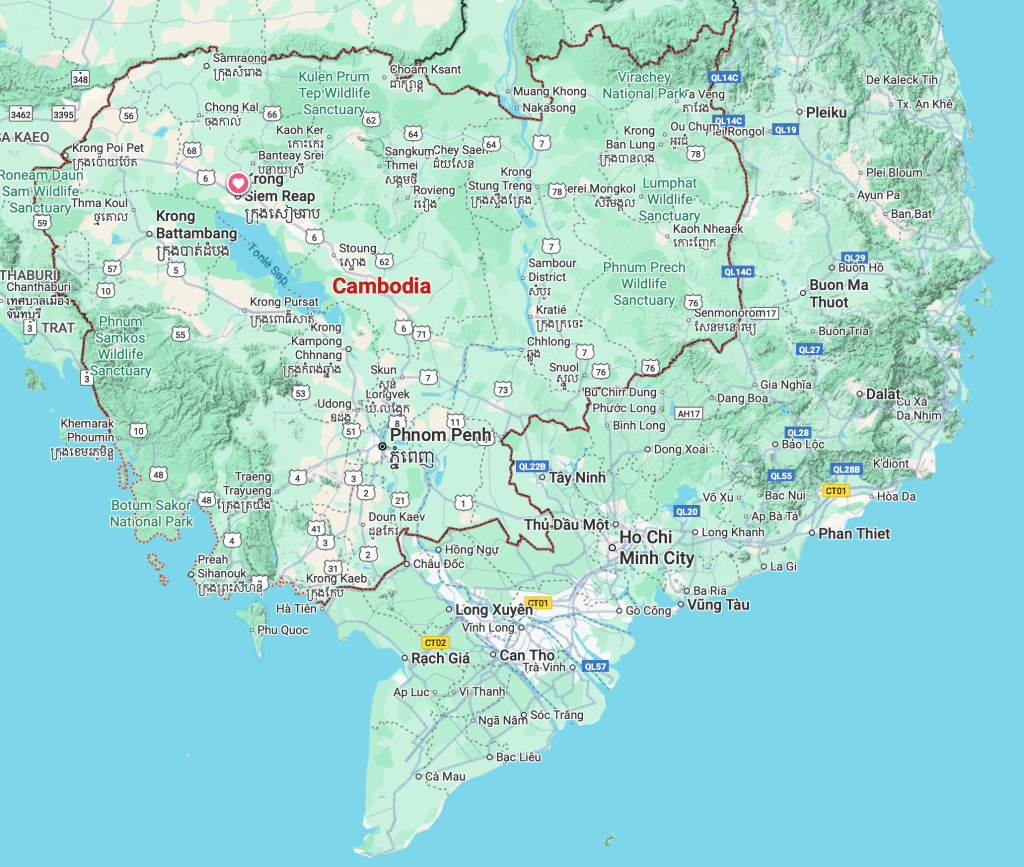

I think this is a good place for a bit of geographical nerdery: the interplay between the Tonle Sap and Mekong rivers is fascinating. Most of the year the Tonle Sap is a tributary of the Mekong. The rivers come together at Phnom Penh and then flow out through the south end of Vietnam into the ocean.

However, during the dry season (which is when we were visiting), the flow in the Tonle Sap river declines, and eventually the Mekong overwhelms the lesser river and flow back up its channel into the Tonle Sap lake, which occupies the center of Cambodia. That fills up the lake, until rains up in the mountains return and let the Tonle Sap river push out into the Mekong again.

This means the lake level varies enormously, and consequently there are no major towns or roads along the lake shore, because the lake shore doesn’t stay put. As Zhou Daguan described centuries ago, “The high water mark around the Freshwater Sea can reach some seventy or eighty feet, completely submerging even very tall trees except for the tips. Families living by the shore all move to the far side of the hills.” The only time during our visit to Cambodia that I actually saw its most prominent geographical feature was when we were leaving and I glimpsed the Tonle Sap lake from the window of our airliner.

My personal, not-a-geologist theory is that at one time a lot of that region was ocean, and the Mekong and Tonle Sap rivers flowed separately into a gulf occupying most of modern Cambodia. But as the Mekong’s delta extended out into the sea, it eventually blocked and captured the Tonle Sap, creating the back-and-forth flow already described. With two rivers’ worth of silt flowing into it, the lake in the center of Cambodia gradually shrank, becoming the modern Tonle Sap lake and the flat, wet, super-fertile land around it.

Once the sky was dark we returned to the dock and went over to the “Magnolia” restaurant for Giant Turmeric Pancakes. They were pretty Giant, too, about a foot across. I had expected something like a crepe, where you wrap the Giant Pancake around stuff and eat it, but they’re actually more like the Banh Hoi we had for lunch — there’s shrimp and vegetables embedded in the Giant Pancake so you tear off a piece and eat it wrapped in lettuce and dipped in sauce. One gets very sticky during this operation.

Which brings me to an important bit of Old Indochina Hand advice for travelers: bring some paper towels. All the non-cloth restaurant napkins I encountered in Cambodia and Thailand were indistinguishable from Kleenex tissues. They can absorb approximately 0.001 cubic centimeter of liquid before turning into a soggy mess, and have the tensile strength of a soap bubble. Any kind of sticky food leaves one with bits of napkin adhering to one’s fingers. Someone could make a fortune selling Bounty or Brawny paper towels in southeast Asia, but until that time, bring some of your own, or a big handkerchief you don’t mind getting food stains on.

After our Giant Pancakes we took a stroll along the Phnom Penh riverfront downtown. I don’t know if it’s like that every night, or maybe everyone was gearing up for New Year’s Eve, but there was a kind of street fair set up along the avenue by the river, with traffic blocked off and a line of vendors stretching for a couple of kilometers at least. And everyone was out there — the crowd must have numbered in the tens of thousands. Everyone was out enjoying themselves, plenty of families with kids, all flowing around the little knots of slow-moving foreigners like ourselves.

Too full from our Giant Pancake dinner, we didn’t partake in much of the street food on display beyond some sweets our guides picked out. I think they were still concerned about food safety, but everything looked pretty thoroughly cooked.

And so after a sobering morning and a delightful evening, we went back to the hotel and made sure we were packed for the next part of our journey.

Next time: Road Trip!

One response to “The Great Indochina Expedition, Episode 3: Emotional Whiplash Day”

[…] Next time: a nice day, with horrors. […]

LikeLike