Hellstrom’s Hive is a novel by Frank Herbert, better known as the creator of Dune. He wrote it in 1972, inspired by a somewhat obscure film by David Wolper called The Hellstrom Chronicle.

I haven’t seen the movie, but I gather it’s an odd combination of a nature documentary about bugs, coupled with some alarmist narration by the fictional entomologist “Dr. Nils Hellstrom” about how insects, with their “communal society” will eventually supplant humanity. (Non-fictional entomologists are probably suppressing laughter at the idea that insects, as a group, are better at cooperating than we are. A caterpillar which just got injected with wasp larvae might also have some opinions.)

Herbert’s novel is more like a hybrid of science fiction and spy novel, or even a proto-“technothriller” than just a book about bugs. It’s about a secret American national-security bureau, known only as “the Agency,” which has a very broad and vague mission and an institutional culture based on ludicrous (but not unrealistic) levels of bureaucratic infighting and paranoia. Some documents about a mysterious “Project 40” have fallen into the Agency’s hands, and they’ve learned that the papers are connected to a scientist named Dr. Nils Hellstrom, who lives on a remote farm in Oregon and makes documentaries about insects.

My personal theory is that Frank Herbert saw the Wolper film and decided to write a novel about the fictional Hellstrom, so that the semi-fictional real world film would be (in the novel) one of Hellstrom’s productions. The novel is liberally studded with quotations from Hellstrom’s work, but I don’t know if those are actually from the movie or not. As far as I’m aware, Herbert’s book is not any kind of authorized novelization of the film.

Needless to say, in the book Nils Hellstrom is not just a humble documentarian. He is in fact one of the leaders of a community called the Hive, hidden underneath the Oregon farm. The Hive is, well, a hive, modeled on the social insects, particularly ants. It’s got tunnels for food production (they use hydroponics, which is a bit curious because a farm could just, well, farm without attracting any attention); it’s got startlingly strong workers who communicate by hand-gestures and pheromones; it’s got giant-headed scientists who can invent super-technology beyond anything The Agency has; it’s got “security” specialists who go out at night and harvest every vertebrate animal on the surface of the farm territory using night-vision masks and weird stun-wand weapons.

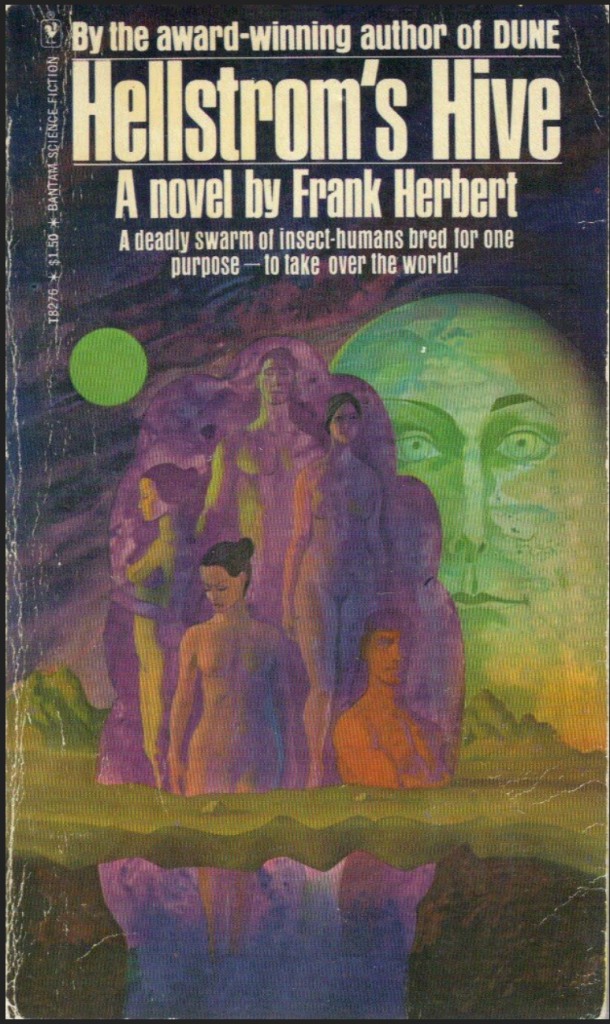

Everyone’s naked (for sound reasons of heat management, of course). And, as the back-cover text on my 1970s paperback copy is very careful to mention, the Hive has “hormones for endless hyped-up sex orgies.”

Did I mention this book was written in the 1970s?

When the first secret Agency operative comes snooping around Hellstrom’s farm disguised as a bird-watcher, the Hive captures, interrogates, and kills him — sending his body, like all animals they catch (and dead Hive members), to “the Vats” where he is reduced to protein. The Agency responds by sending two agents, which is where the action of the novel actually begins. (Which means there will be spoilers ahead for a book more than 50 years old.)

Those two also get caught, interrogated, and put on the daily special for tomorrow’s lunch. The Agency, true to form, sends an even bigger team. This bunch has orders to make friendly contact with Hellstrom, and try to find out more about “Project 40” because some Agency higher-ups think it might be the key to valuable improvements in metallurgy.

The leader of the Agency’s field team is a man named Peruge, who manages to meet with Hellstrom — accompanied by the local deputy sheriff, who is a Hive operative himself. The meeting is inconclusive because Peruge’s veiled hints about metallurgy go completely over Hellstrom’s head. The metallurgical applications are a relatively minor spinoff of Project 40, which is really an apocalyptic superweapon capable of literally destroying the Earth.

But Fancy, one of the women of the Hive, sneaks out and bicycles to Peruge’s motel, equipped with a drug patch so the two of them can have one of those endless hyped-up sex orgies mentioned on the cover. Apparently she’s drawn to Peruge because he’s got genes the Hive lacks. That’s one interesting difference between Hellstrom’s Hive and real-world insect colonies. Bugs don’t want diversity; everyone in the hive is a sister or niece.

Unfortunately for the Hive, Peruge dies after his endless hyped-up sex orgy with Fancy, and she gets recovered by some Hive operatives so the Agency can’t get her. But the minions of the Agency do have her bicycle, which belonged to one of the previous sets of dead Agents investigating the Hive. Hard evidence. Now they can threaten all kinds of law enforcement and national-security mayhem. Frank Herbert was a reporter and political speechwriter before he hit it big as a science fiction writer, so he absolutely nails this kind of official mindset — can’t make an overt move unless you’ve got “probable cause,” but then the gloves can come off.

Janvert, the next agent in line to run the Oregon operation, goes to the farm and confronts Hellstrom. The response? True to form, the Hive captures and interrogates him, drugging him to start making him part of the Hive himself. But Janvert, unlike every previous Agency operative, manages to escape in a pretty impressive James Bond movie climax sequence. In the course of his escape we also get an inadvertent tour of the Hive itself. Turns out it’s huge, with something like fifty thousand inhabitants and tunnels extending kilometers underground, all hardened with some kind of ultra-tech concrete that’s even proof against atomic weapons.

But just as the Agency is about to unleash the FBI and the Army and who knows what else, the Hive plays their trump card. They show what Project 40 is really capable of, by causing an undersea volcanic event which creates a new island off the coast of Japan. (And, presumably, a lot of tsunami damage around the Pacific basin.)

The book ends inconclusively. The Agency knows about the Hive now, but its leaders are afraid of Project 40 and still hope to exploit the Hive’s technology. Meanwhile the Hive is getting ready to swarm, sending out cells to start new Hives all over the world . . .

So, is it a good book?

It’s weird. I can’t avoid the suspicion that Frank Herbert wanted to take the piss out of some of his more hippie-ish fans when he wrote this. Consider: the Hive is a rural commune full of people who live without conflict and share everything (including protein). They’re naked, they recycle, they make extensive use of consciousness-altering substances — and endless hyped-up sex orgies! — and they’re getting hassled by The Man in the form of the Agency. One can see the Hive as almost an aspirational ideal for the Sixties counterculture. If this book was by Ted Sturgeon they’d probably be the unambiguous heroes.

Moreover, like a lot of stories involving embattled counterculture enclaves — like Stranger in a Strange Land, or Stapledon’s Odd John or even Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead — the author seems to be massively stacking the deck in favor of his pocket Utopia. They’re nuke-proof, they’re all loyal and incorruptible, they have secret influence extending well beyond their borders, they’ve got an unstoppable super-tech weapon, and their main antagonists are massively self-sabotaging. It really does feel as though we’re supposed to cheer on the Hive as they stick it to Nixon and the Agency. Right on!

Except . . . even though most of what we see of the Hive is through the viewpoint of its own loyal members, it’s still relentlessly creepy. The giant-headed scientists ride around carried by mindless slave workers, like the character “Master Blaster” in Beyond Thunderdome. Most of the Hive’s reproduction isn’t done by women like Fancy, but rather by “stumps” — headless, limbless pregnant torsos. The endless hyped-up sex orgies are as impersonal and affectionless as a truck-stop glory hole. It all makes The Handmaid’s Tale look like a Harlequin romance by comparison.

Few of the Hive members really even think as individuals at all, and as the novel goes on we see that even Hellstrom himself isn’t so much a leader as an appendage of the Hive’s collective will, with little real agency of his own. And if you’re rebellious, or fail at your task, or are no longer of use to the group, there’s always the Vats.

Not very groovy. That career in plastics looks better all the time.

The result is a book with nobody the reader really roots for. Maybe Agent Janvert as an individual, fighting both the Hive and struggling with his own bosses (and one of the only characters in the entire story shown with a genuinely loving relationship with another person), could be the protagonist, but he is a minor character for the first half of the novel. For most of the book our viewpoints are the deeply unpleasant Agent Peruge or the Hive commissar Hellstrom.

The text also shows a lot of Frank Herbert’s stylistic quirks. The internal monologues, the constant jumping around among viewpoint characters in a single scene, the excerpts from imaginary books and diaries, and the sense that individual characters are being jerked around by impersonal evolutionary forces — all of that should be very familiar to readers of his Dune books. If you like it, fine. If you find it grating, well, it’s going to grate.

He does show off his strengths, too: sound science (the biology hasn’t aged badly in half a century), solidly worked-out cultures, and an old-school newspaperman’s clear and unsentimental eye for human behavior. Herbert was definitely at the top of his game when he wrote this one.

And Herbert’s central concept — the Hive itself — is utterly fascinating. His depiction of it and how it operates is the book’s main appeal. Basically, if you’re willing to put up with reading about a bunch of jerks acting like jerks to other jerks who are being jerks, your reward is a very well-realized picture of a truly alien society, far stranger than 90 percent of the extraterrestrials in science fiction, then or now.

It’s also worth noting that this novel would be easy to make into a roleplaying adventure. The obvious candidates would be contemporary horror-investigative games like Call of Cthulhu, Delta Green or Fall of Delta Green. Fall of Delta Green even has the right time period: just send the operatives to Oregon because of some strange rumors and run the novel as-is. The Hive fits very neatly into a Lovecraftian setting. You can link it to the callous and manipulative Mi-Go or the ancient cannibal hives of the Delapore and Martense families.

However, the Hive is sufficiently versatile that one could drop it into almost any game setting. It has apparently existed for centuries, so a group of Wild West cowboys or steampunk adventurers might find out there’s something mighty funny going on up in Oregon or on an eccentric European nobleman’s private island. A company of swashbuckling Musketeers could stumble across an insect-obsessed community in some remote part of the Pyrenees.

In science fiction campaigns, Traveller gamemasters can drop a Hive-inspired human society onto any random planet their players decide to visit (Government Type 2 if you like the Hive, 9 or C if you don’t; Law Level C either way). Amp up the Hive’s super-science and they could even be adversaries for comic-book style superheroes in a Champions or Mutants & Masterminds game. Hellstrom’s farm would be a great addition to any post-apocalyptic game like Gamma World or the Fallout setting — at first it looks like a bright enclave of stability and civilization, but then you start to realize this might be the future for humanity.

It would be harder to fit the Hive into a Star Trek game, if only because it’s too similar thematically to the Borg, and the creepy nastiness goes away if the Hive is an alien species who just evolved that way. And it’s a bit too “NC-17” for a Star Wars game.

Hellstrom’s Hive has a sister in the fantasy realm: the human anthill kingdom of Quarmall in Fritz Lieber’s Fafhrd and Gray Mouser story “The Lords of Quarmall.” Unlike the Hive, Quarmall isn’t a collective intelligence, but it does have the deep underground tunnels, the mindless slaves, and uses mind-control magic in place of pheromones. One could probably work up a mashup of the two hive-societies for a D&D campaign, although in a world with goblins and orcs and gnolls, the Hive denizens lose some of their horror, becoming just another monster race to stab.

My overall impression: Hellstrom’s Hive is a very interesting book with a great central concept and almost no likeable characters. It’s not a “fun read” but it’s definitely worth reading.